Thanks again to e pluribus munu for contributing these posts on the 1890s Baltimore Orioles. if you’ve written something you’d like to share with the HHS community, drop me a note at doughhs@hotmail.ca.

In his first post, epm identified that Orioles’ manager Ned Hanlon completely overhauled the Orioles’ personnel and style of play over the space of two years, from 1892 to 1894, and, in doing so, turned a last place team into a championship club. In part two, epm takes a closer look at this new style of play and its influence on the major league game. More after the jump.

How Did the Old Orioles Win?

The focus of this post is how the Old Baltimore Orioles, perennial doormats, an “expansion” franchise, and dead-last-by-a-mile in 1892 became the dominant power in the NL by 1894. The larger issue is why this particular team turn-around would have a great enough impact on the game to warrant being considered the key element dividing “early” and “modern” baseball.

Ned Hanlon’s Transformation of the Orioles, 1892-94

Let’s start by dissecting the steps Orioles manager Ned Hanlon took to turn the team around, bearing in mind that Hanlon’s boss, Harry Von der Horst, provided Hanlon with limited financial resources, but exceptionally broad discretion to act.

- Hanlon initiated wholesale personnel changes, beginning to clear house within weeks of taking charge, but only gradually, through many releases, trades, and re-trades, finding his way to the team he wanted.

- The design of Hanlon’s team favored young, malleable players. He viewed the value of a player in terms of his potential to contribute to his particular team, rather than to his general talent. Three of the Orioles’ “Big Four” stars (Hughie Jennings, Joe Kelley and Willie Keeler) were acquired through trades in which they were an “added” player (the fourth, John McGraw, was inherited as a teenage player, a great stroke of luck for Hanlon and one which he had the acumen to recognize).

- The team was governed by a simple, unifying strategy guiding his players’ approach to game situations: do what your opponent does not expect.

- Hanlon developed a tactical playbook for surprising opponents. Its elements emphasized “small ball” tactics, which were more subject to hitter control (examples include the hit-and-run, the sacrifice and the bunt base hit, the intentional foul, and the “Baltimore chop”). The playbook extended to base-running and to fielding (e.g. outfield and infield cut-off plays, double play choreography, etc.).

- Hanlon demanded intensive drilling to master the playbook. He was relentless.

- Hanlon drew ideas from others, including his own players, to whom, in certain cases (particularly McGraw), he was willing to give exceptional autonomy.

- Hanlon viewed winning as the only goal, and willingly developed or authorized any tactic that contributed to that goal (this is where the cheating and rowdiness come in, but other things as well, such as the modification of the home field to accommodate his team’s tactics and talents).

Note the absence of pitching tactics. So far as I can tell, Hanlon, himself a center fielder, had little to offer his pitchers. However, Hanlon nevertheless managed to coax memorable seasons out of a string of forgettable pitchers (ever heard of Bill Hoffer? Arlie Pond? Joe Corbett?), largely, it appears, by perfecting the defense behind them.

Because of the economic depression following the Panic of 1893, team owners in 1894 suspended the former custom of sending their teams south for spring training. Hanlon, however, demanded that owner Von der Horst pony up, and so the Orioles alone traveled away from home, assembling all players for a training camp in Macon, Georgia. Unlike the relaxed spring training routines typical of that time, Hanlon ran the Macon operation like a boot camp, identifying players’ weaknesses and prescribing constant drill through all-day training (Hughie Jennings’ description was, “Work, work, work, work, all the time.”). When the team returned north to open the season against New York, Giant manager John Ward took note of the Orioles’ southern trip in speaking to the press, commenting on its energizing effect and even predicting that the Baltimores might take one of the three games in the opening series between the clubs (after all, the Orioles’ reputation was still as a losing team, with a 106-171 record over the prior two seasons). In fact, the “new” Orioles swept the Giants and were off on their championship run.

What went on in Macon and its aftermath bears little resemblance to “early” baseball. Although some specific aspects of the Orioles’ tactics were later banned or went out of style, Hanlon’s strategic approach to team building, player training, and in-game maneuvering is consistent with the features of baseball up to the early 1920s and beyond.

The Orioles as Champions

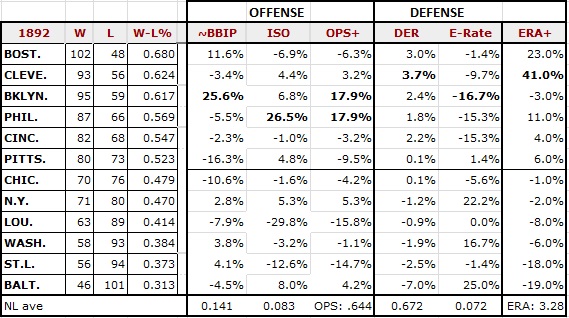

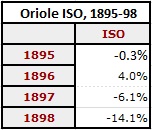

The results of Hanlon’s efforts are plain enough when we compare the Oriole team stats in 1894 to the 1892 team he inherited. Those two seasons straddle the introduction of the 60′ 6″ pitching distance and also the reduction in the league schedule from 154 games to 132. But, if we convert all stats to deviations from league averages, the playing field will stay level across that divide. When we do that, the transformation that we see in the Orioles’ place in the standings is clearly reflected in their offensive and defensive statistical profiles, as shown below, comparing NL team stats in 1892 and in 1894.

[In these charts, in addition to the ersatz “small ball” category of ~BBIP (the formula is ~BBIP = (BB+SB+HBP+SH)/PA), I’ve included both DER and also the teams’ “Error Rate,” which is no more than the inverse of fielding percentage (that is, percent of fielder chances resulting in errors), expressed as a percentage deviation from the league norm. I’ll have something to say about this below.]

Let me list some of the key observations:

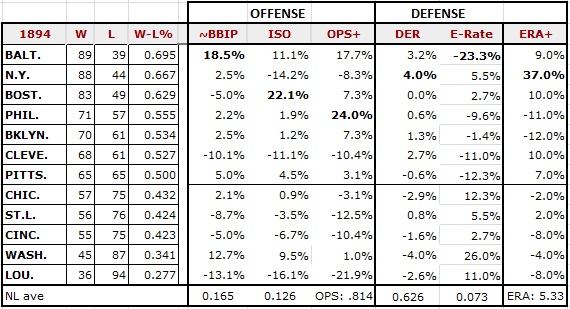

1) Looking at ~BBIP, the Orioles went from being sub-par in their “small ball” approach (playing for one base and one run at a time), to being the team most adept in this aspect of the game. This holds true even if you consider productivity in singles – the small-ball batting event that ~BBIP does not include. In terms of all offensive “one-base events” (call these “1BE”), the Orioles led the league, though by a much smaller margin (because the Phillies’ famous .350 team BA in 1894 was actually the product of a huge number of one-base hits). The Orioles’ league domination in the categories of ~BBIP and 1BE persists throughout Hanlon’s tenure, as shown in the figures, all of them league-leading, in the table to the right.

1) Looking at ~BBIP, the Orioles went from being sub-par in their “small ball” approach (playing for one base and one run at a time), to being the team most adept in this aspect of the game. This holds true even if you consider productivity in singles – the small-ball batting event that ~BBIP does not include. In terms of all offensive “one-base events” (call these “1BE”), the Orioles led the league, though by a much smaller margin (because the Phillies’ famous .350 team BA in 1894 was actually the product of a huge number of one-base hits). The Orioles’ league domination in the categories of ~BBIP and 1BE persists throughout Hanlon’s tenure, as shown in the figures, all of them league-leading, in the table to the right.

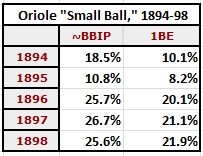

2) The Orioles showed considerable power, reflected in their 1894 ISO figure, second only to Boston’s. This was the product of a late move by Hanlon to trade for an experienced veteran and power hitter, Dan Brouthers, a former teammate of Hanlon’s (on the 1886-88 Detroit Wolverines).  Hanlon was apparently hedging his bets on his full commitment to one-run tactics, but more important, going into the season with the youngest team in the league, Hanlon wanted to anchor the clubhouse with a steady veteran whose outstanding career record could command respect (an attitude Wilbert Robinson, the 30 year-old team captain, was less able to command). Brouthers did what Hanlon had hoped, and led the team in HRs with 9, in spite of which, the Orioles were last in the league in that category. With the team stabilized, Hanlon sold Brouthers in May 1895, and went all-in on the one-run approach. The team was thereafter most often below league average in ISO, as shown in the table to the right.

Hanlon was apparently hedging his bets on his full commitment to one-run tactics, but more important, going into the season with the youngest team in the league, Hanlon wanted to anchor the clubhouse with a steady veteran whose outstanding career record could command respect (an attitude Wilbert Robinson, the 30 year-old team captain, was less able to command). Brouthers did what Hanlon had hoped, and led the team in HRs with 9, in spite of which, the Orioles were last in the league in that category. With the team stabilized, Hanlon sold Brouthers in May 1895, and went all-in on the one-run approach. The team was thereafter most often below league average in ISO, as shown in the table to the right.

3) The Orioles’ fielding went from low comedy to professionalism, as the turnaround in their DER shows, going from 7.0% below league average in 1892 to 3.2% above in 1894 (though, in absolute terms, DER suffered significantly due to the 1893 rule changes, falling league-wide from .672 in 1892 to .626 in 1894). The Giants made a similar turnaround over those two seasons, going from a DER 1.2% below league average to a league-leading +4.0%, but how they accomplished that result was quite different from how the Orioles did it.

The Giants’ fielding improvement partly reflected more sure-handed fielders who made 22.2% more errors than the average 1892 team, but only 5.5% more in 1894. But, since the latter figure was still above league average, the Giants’ leading 1894 DER must be based on having more “fieldable BIP”, resulting in improved fielder range. From the Giants’ outstanding 137 team ERA+ figure (Amos Rusie and Jouett Meekin combined for 69 wins in over 850+ IP, earning 25.4 WAR), we can surmise that their high DER was principally a function of terrific pitching generating more easily fieldable balls in play. But, such was not the case for the Orioles, whose ace pitcher (Sadie McMahon) earned only 6.0 WAR with the rest of the staff adding only 10.5 WAR more. While their pitching was good enough, as we will see, it is more likely that Baltimore’s above-average ERA+ was the product of relatively flawless fielding, rather than their fielding improving because of stellar pitching, as was the case for the Giants.

The Modern Pitching Staff

This brings us to pitching and the final theme I want to deal with in this post: the Orioles’ modest pitching talent and the added burden this placed on a manager having to compensate for that weakness (which continued throughout Hanlon’s tenure with Baltimore).

Hanlon inherited a bad pitching staff with a proven ace: Sadie McMahon. But, McMahon’s arm had peaked at age 23 in 1891, and by August 1894 he had encountered the arm trouble that would end his career, recording only 21 more wins before retiring in 1897. From 1895 on, Hanlon was continually patching together pitching staffs led by nonentities having peak years. Lacking truce aces, the Orioles of the mid-1890s pioneered an evenly distributed four-man rotation. In 1897, Hanlon’s four top starters pitched 26%, 25%, 21%, and 18% of the team’s innings, and in no year after 1893 did an Oriole starter pitch more than 28% of the team’s innings. For the 1894-97 seasons, primary starters averaged 26% of team IP and 6.5 WAR, with the peak WAR season for any starter only 8.7, accomplished in an extraordinary 1895 rookie campaign by Bill Hoffer.

In contrast, the Orioles’ most persistent challengers, the Boston Beaneaters and Cleveland Spiders, could invariably rely on strong seasons from the two best pitchers of the era, Kid Nichols and Cy Young. Over the 1894-97 period, Nichols averaged 33% of Boston’s innings and 9.1 WAR, while Young’s figures were 33% of IP and 9.9 WAR. If the Giants had not botched Rusie’s career, they would have been in the same sort of situation. Moreover, all three of those pitchers were backed up by terrific number-two starters (Jack Stivetts in Boston, George Cuppy in Cleveland, and Jouett Meekin in New York). Over those four seasons, Boston and Cleveland realized 45% and 62% of their total team WAR from their pitchers, compared to just 36% for Baltimore.

Reliance on a dominant ace is one common feature of many early baseball championship teams, from Al Spalding, to Ol’ Hoss Radbourne, to John Clarkson, to Tim Keefe. When the Giants won the 1889 pennant with Keefe recording a team best 28 wins, it was then the lowest leading total on any championship team (undoubtedly attributable to Mickey Welch backing him up with 27 W’s). The Orioles lowered that mark in 1894, when their ace McMahon recorded 25 wins, but his number two, Bill Hawke, added only 16 victories. This was something entirely new! Bill Hoffer’s great 1895 season (31 wins) gave Hanlon a break, but the final championship team in 1896 duplicated the 1894 club with Hoffer logging 25 wins and Arlie Pond adding 16. The 1897 club fell just short (two games back of Boston) but Hanlon’s four starters, with win totals of 24, 22, 20, and 18, looked like Earl Weaver‘s Orioles of 75 years hence.

I think that’s enough for this post. If there is interest, I’ll add a final post on how I think Hanlon’s Orioles could be best said to have captured and crystallized modernizing trends that began in the mid-1880s, rather than to have “invented” something new, and also how I think that crystallization was transformative for baseball. Modern elements had been appearing in early baseball, from the mid-1880s or even earlier; the Orioles added some new twists, but their essential function was to bring together many of these disparate modern elements within a consistent strategic and organizational vision. Their spectacular results would influence the perception of team professionalism at the major league level.